Using Stem Cells to Fight Lung Disease

By Kevin Ritchart

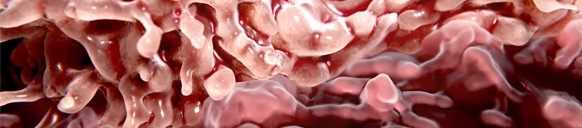

Everything is easier in 3D. That’s the tack being taken by researchers from the Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at UCLA who have succeeded in creating three dimensional lung organoids from stem cells.

These lab-grown tissues can be used to study lung diseases like idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, which is difficult to do using conventional methods. Typically, scientists are forced to rely on two dimensional cell cultures to study the effect of genetic mutations or drugs on lung cells. But the problem with taking a 2D approach to the study of a disease like idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is that flat cell cultures taken from people with the disease appear healthy rather than showing the scarring present in those who have the disease.

“Scientists have really not been able to model lung scarring in a dish,” said Brigitte Gomperts, MD, associate professor of pediatric hematology/oncology and a member of the UCLA Broad Stem Cell Research Center. “While we haven’t built a fully functional lung, we’ve been able to take lung cells and place them in the correct geometrical spacing and pattern to mimic a human lung.”

How It Works

The process of getting stem cells to mimic the makeup of lung tissue begins with the coating of tiny gel beads with lung-derived stem cells and letting them assemble into the shape of air sacs found in human lungs. This approach to growing 3D stem cells into organoids (organ buds grown in vitro that contain realistic organ anatomy) for the purpose of research began in 2010 and has been identified as one of the most important scientific breakthroughs of this decade, according to The Scientist magazine.

“The technique is very simple,” said Dan Wilkinson, a graduate student in the UCLA Department of Materials Science and Engineering and one of the authors of the research paper on this subject. “We can make thousands of reproducible pieces of tissue that resemble lung and contain patient-specific cells.”

By studying these patient-specific cells, scientists will be better equipped to hone in on the causes of diseases like idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and aid in developing more effective treatment options. The primary indicator of the disease is scarring of the lungs that makes them thick and stiff .

Over time, this causes patients to experience a progressively worsening shortness of breath and a lack of oxygen getting to the brain and vital organs. Once they’re diagnosed with this disease, patients typically live about three to five years.

The Next Steps

At this point, researchers don’t know the cause of all cases of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. For some, it’s been found to run in their families. For others, smoking and exposure to certain types of dust have been known to increase the risk of developing the disease.

With the development of the new lung organoids, researchers will be able to study the biological causes of diseases and identify the best courses of treatment. This would involve collecting cells from the patient, turning them into stem cells, forming them into 3D organoids and putting those organoids through a battery of tests. Because it’s easy to create multiple organoids at once, researchers are able to test the effects of multiple drugs at the same time.