First Wine Makers May Have Been European

By Christina Phillis

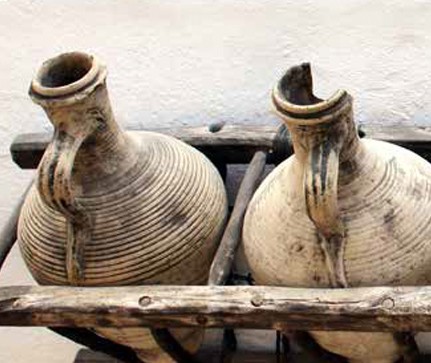

Where the best wine comes from is an ongoing debate, but who was first to the table may be a settled matter, according to a new study. By using a new method to analyze liquids absorbed by clay containers found in Northern Greece, researchers may have unlocked the mystery of where grape-based wine originated. The two pieces of a smashed jar and intact jug used for this research were discovered in the ruins of a house destroyed by a fire around 6,300 years ago at an ancient farming village. Scientists successfully identified chemical markers of both grape juice and fermentation in clay powder scraped off the inner surfaces of the clay vessels.

The True Test

To determine whether or not the liquid embedded in clay is actually wine, one needs to identify the presence of both dark grape, which includes tartaric, malic and syringic acids, as well as fermentation markers, such as succinic and pyruvic acids.

Aldaric acids, such as tartaric, are more deeply bound to the clay structure than previously thought. They can’t be extracted using simple solvent extraction, but must instead be detected using a technique called second acido-catalyzed extraction. To achieve the sensitive detection of fermented grape biomarkers, chromatography must be coupled with mass spectrometry. Using replicas of the clay containers, which were filled with wine and then emptied, scientists were able to prove the success of this new technique on other vessels. The remains of pressed grapes consisting of loose pips, skins, and pips still enclosed by skin found in association with the jar already indicated the production of either wine or grape juice by the farmers of this village, according to chemist Nicolas Garnier of École Normale Supérieure in Paris and archaeobotanist Soultana Maria Valamoti of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece. Identification of fermentation markers in the clay jugs further corroborates this idea.

Past Findings

In previous reports of ancient wine creation, researchers could only rely on the identification of the chemical markers of grapes. Without the ability to detect the process of fermentation needed to turn the grapes into wine, one could assume that other containers were used to hold grape juice. This is the problem with jars discovered in Iran from 7,400 years ago. Pottery fragments found in China dating back 8,000 to 9,000 years indicated that people in that location and time period likely made wine from rice, honey and fruit.

Artifacts found in an Armenian cave dating back 6,100 years are evidence of the first known winery. Not only did they find pottery containing traces of malvidin, the plant pigment responsible for wine’s red color, they also found a wine press for stomping grapes, fermentation and storage vessels, drinking cups, and withered grape vines, skins, and seeds. Given the difficulty in identifying the true indicators of wine, researchers believe this new method has broad applications for detecting wine traces in different kinds of archeological artifacts or structures in the future.