Lab Collab: Teaming Up to Take Down Parkinson’s

By Kylie Wolfe

In March of 2018, the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research announced its PATH to PD program, a two-year, $6 million grant initiative designed to explore disease onset and progression. The funding was divided equally between three labs, one at the Pittsburgh Institute for Neurodegenerative Diseases, one at Northwestern University, and the other at the National Institute on Aging.

These labs were encouraged to communicate and collaborate regularly, sharing ideas and insights along the way. For the last year and a half, they’ve investigated three areas known to contribute most to Parkinson’s disease: genetics, environment, and age. Researchers believe the disease is triggered by a combination of these factors, making this program fairly comprehensive.

Understanding the Disease

Currently, the only treatments available for Parkinson’s patients merely mask symptoms rather than slow or stop disease progression.

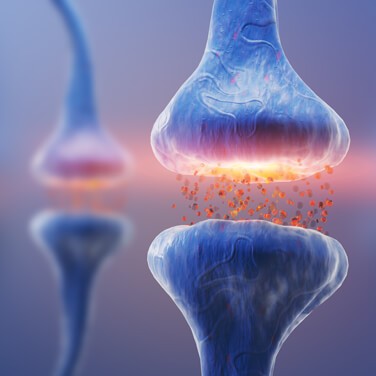

Symptoms develop slowly, and each person’s experience is different. But what’s true for everyone is the loss of neurons in the substantia nigra, which is part of the midbrain. Cells in this region release dopamine, a neurotransmitter or chemical messenger that aids in body movement. Without sufficient neuron signaling and dopamine release, patients develop a variety of movement-related symptoms, including shaky, slow, and rigid motions and trouble balancing.

The researchers participating in this grant want to better understand the causes of the disease, first and foremost, in the hope that their work might lead to the development of more effective treatments.

Progress in Pittsburgh

Under the guidance of Dr. Timothy Greenamyre, scientists at the Pittsburgh Institute for Neurodegenerative Diseases are tackling four main projects related to environmental and genetic factors. The first examines environmental toxins to see if they activate LRRK2, a gene associated with Parkinson’s. Establishing a biological mechanism could uncover a relationship between two causes of the disease.

Their second project investigates calcium signaling within neurons and the role of alpha synuclein, a protein that accumulates in the brains of Parkinson’s patients.

A third project seeks to determine if dopamine is toxic when given to patients in response to concerns that Levodopa, a common drug treatment used to increase dopamine levels, may accelerate neurodegeneration. The goal here is to find neuro-protective therapies that slow or stop progression of the disease.

Their fourth study is designed to find biomarkers that can help create a blood-based test for disease detection. These biomarkers would be associated with LRRK2 activity and peripheral white blood cells.

Making Strides in Chicago

Researchers at Northwestern University, led by Dr. D. James Surmeier, are investigating cellular aging, its relation to mitochondrial damage, and overall connection to the disease.

“We decided to attack aging in a different way than people had done before and that was to use genetic tools to introduce aging-related changes in dopaminergic neurons, but then look at the consequences of those changes in a young mouse,” he said. Taking this approach kept the circulatory and respiratory systems from being compromised like they would be in an older animal.

Their first target was mitochondrial dysfunction, something that can be triggered by oxidative stress. The researchers knew that both Parkinson’s patients and healthy aging patients experience the loss of complex I function, a protein complex within the mitochondria, but they wanted to learn more.

Surmeier and his team chose to knock out a subunit of complex I, eliminating the mitochondria’s ability to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), a necessary energy source, especially for neurons.

To their surprise, even though ATP wasn’t being generated, the cells didn’t die.

“The possibility of restoring [dopaminergic neuron] function even with advanced disease is a potentially interesting avenue of study. We would never have gone down that path if we weren’t given the opportunity to do something out of the box, very exploratory, and high risk,” said Surmeier.

For now, there is no treatment that targets complex I, but understanding this mechanism could open doors for potential therapies.

Beginnings in Bethesda

At the National Institute on Aging, Dr. Andrew Singleton and his team are focused on mapping genetic changes related to the disease.

Their initial series of experiments looked at 100 iPS lines, or induced pluripotent stem cells, from participants both with and without Parkinson’s disease to produce complete genetic information and an assessment of each person’s genetic risk.

The team is mapping molecular markers like transcription, DNA methylation, and protein levels to see the relationship between these points of interest and known genetic information to better understand disease risk.

“It’s really forcing us to bring together complex genetic information and complex functional information in a meaningful way,” said Singleton. Through this project, they want to create a resource that explains how genetic factors affect the disease pathway.

He emphasized that his team’s efforts are really just the beginning. “In many ways it’s a pilot grant because we know we’re not at scale to do what we want to do. It is, however, an amazing beginning, really only possible because of this innovative funding program. The hope is to expand this to a larger series with more measures and more outcomes.”

Collaboration is Key

PATH to PD is especially unique, requiring the awarded labs to communicate at a high level over the duration of the program. Their research is intended to be interactive, exploratory, and flexible.

“These are some of the best labs in the world in terms of PD and they each have resources and technologies and interests that can help each other. It’s been very enlightening,” said Greenamyre.

“All of us have demonstrated that we know how to do science and are committed to the effort. [The foundation] knew we could make good use of the money and learn something important, even if our hypotheses were wrong,” said Surmeier, who sees the grant program as an incubator for innovative research.

The groups interact regularly to share data and update each other on their progress. Monthly calls give researchers the opportunity to share their current findings, suggest new research angles, and make informed hypotheses through their collective results. Discussions are led by post-doctoral candidates from each team, allowing the conversation to flow naturally.

“We also had an in-person meeting where everyone involved got together in Pittsburgh,” said Singleton. This past January, in a city celebrated for being a place where three rivers meet, researchers from the three labs, representatives from the foundation, independent assessors, and other experts in Parkinson’s disease convened to discuss results and deepen relationships.

Greenamyre said he’s passionate about this approach and has also noticed its impact. “Collaboration is really the way of the future. The way of the present, actually. If you want to have a meaningful, impactful study you have to apply multiple analyses that can’t be performed by one lab alone.”

As promising as their work together has been, the researchers are uncertain about what will happen after the program ends. “Two years is a short amount of time to explain a problem and attempt to solve it,” Greenamyre said, specifying that renewed funding for the program is currently not on the horizon.

The labs are looking for ways to continue select projects. Some could lead to more conventional grants from the NIH, while others might foster smaller funding opportunities from the foundation. Regardless, this grant has encouraged thoughtful discussions and allowed these leading labs to work together in a way that uncovers answers to difficult questions.

Grants and Goals for the Future

Through well-funded and specifically targeted grant programs, the Michael J. Fox Foundation hopes to accelerate the path to better therapies and an eventual cure. In February of 2019, the non-profit announced 127 upcoming grants totaling an additional $24 million.

As the foundation continues to fuel Parkinson’s research, its PATH to PD program will soon wrap up its second year. Thanks to the encouragement and flexibility of this grant initiative, these scientists are breaking the stigma of discussing unpublished research, pushing them to work toward a crucial common goal — together.